Cash balance plans are technically defined benefit plans that share some key characteristics with defined contribution plans.

IRS regulations finalized in 2010 and 2014 clarified some legal issues and made these plans more flexible and appealing to employers. As a result, there was a 152% increase in new cash balance plans between 2010 and 2015.1

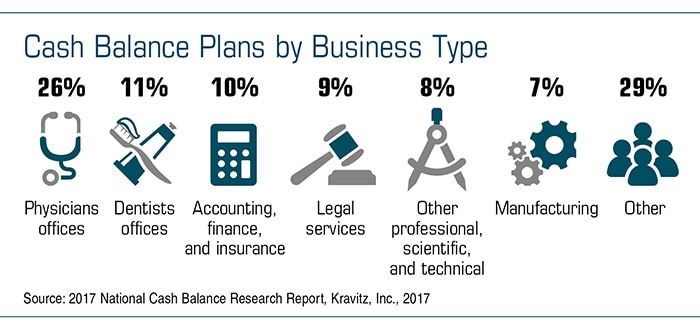

These hybrid plans have generous contribution limits that increase with age, and are often stacked on top of a 401(k) and/or profit-sharing plan. This might allow partners in professional service firms and other high-income business owners to maximize or catch up on retirement savings and reduce their taxable incomes.

In 2017, a 65-year-old could save as much as $251,000 in a cash balance plan, while a 55-year-old could save $184,000 on a tax-deferred basis (until the account reaches a maximum accumulation of $2.5 million).2

Assuming the Risk

A cash balance plan is also a powerful tool for employee recruitment and retention. As with other defined benefit plans, employees are promised a specified retirement benefit, and the employer is responsible for funding the plan and selecting investments. However, each participant has an individual account with a “cash balance” for record-keeping purposes, and the vested account value is portable, which means it can be rolled over to another employer plan or to an IRA.

But unlike a 401(k), the participant’s cash balance when benefit payments begin can never be less than the sum of the contributions made to the participant’s account, even if plan investments result in negative earnings for a particular period. This means the employer bears all the financial risk.

Funding the Plan

Each year, the employer makes two contributions to the cash balance plan for each employee. The first is a pay credit, which is either a fixed amount or a percentage of annual compensation. The second contribution is a fixed or variable interest credit rate (ICR). The ICR can be set to equal the actual rate of return of the portfolio, if certain diversification requirements are met, which reduces the employer’s investment risk and the possibility of having an underfunded plan due to market volatility.

Weighing the Costs

The amount that the employer must contribute to the plan each year is actuarially determined based on plan design and worker demographics. Typically, IRS rules require owners to contribute 5% to 8% of pay to non–highly compensated employees in order to make larger tax-deferred contributions for themselves.3

Businesses may take a significant tax deduction for employee contributions, so current-year tax savings may offset some of these costs. Still, a cash balance plan is typically more cost-effective if you are a sole proprietor or the owner of a small firm with just a few employees.

1, 3) 2017 National Cash Balance Research Report, Kravitz, Inc., 2017

2) Kravitz, Inc., 2016