It’s no secret that state pension funds face fiscal challenges. A 2017 Pew Research study found that the median funded ratio — the proportion of assets to liabilities — dropped from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 72% in fiscal year 2015, with a total shortfall of almost $1.1 trillion. The shortfall was expected to increase in 2016 due to lower-than-expected investment returns.1

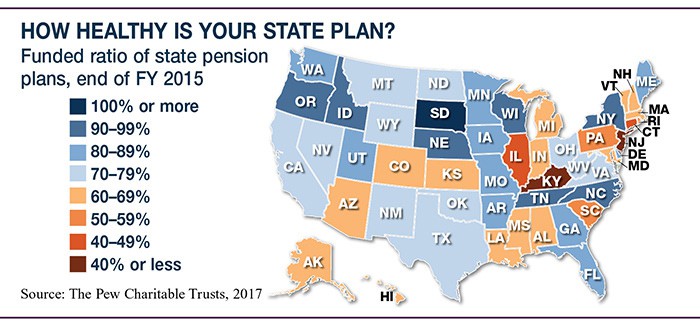

The median is a helpful measure, but there was wide variation among states. On the high end, South Dakota had more assets than liabilities, with a funded ratio of 104%. On the low end, Kentucky and New Jersey had funded ratios of less than 40%, a level associated with fiscal crisis.2–3 Only 18 states had ratios of 80% or higher (see chart).

Obviously, the financial health of a state pension fund can directly affect those who receive or expect to receive pensions. But all taxpayers in a given state may ultimately bear responsibility to help meet that state’s pension obligations.

Leveraging the Future

A funded ratio of less than 100% is not cause for immediate concern, because fund managers expect to make up the difference through investment returns by the time that pension liabilities have to be paid. Plans operate under an “earnings assumption” that typically ranges from 7% to 8% per year.4

During the 1980s and 1990s, when low-risk, fixed-income investments provided higher predictable returns, state pension funds were more likely to stay on target year-to-year. However, low interest rates have forced fund managers to move more assets into equities and other riskier investments. This has resulted in greater volatility, cutting into assets during bad years and making it more difficult to project required funding.5

States have also struggled to fund pensions regardless of returns. The good news is that this improved in 2015, with 32 states achieving “positive amortization” — meaning that contributions would have helped close the state’s funding gap independently of investment returns. This effort may be due in part to new reporting standards implemented in 2014.6

Funding pensions may always be a challenge because of competing budget priorities, but some experts believe states might benefit from reduced earnings assumptions that would encourage more realistic contribution levels.7 In the long run, higher interest rates for lower-risk, fixed-income investments could put pension funds on more solid ground, but until that happens many state funds are likely to remain on the fiscal edge.

All investments are subject to market fluctuation, risk, and loss of principal. When sold, investments may be worth more or less than their original cost.